.

Rebecca Jones (1739-1818), Quaker minister, was born in Philadelphia, the only daughter of William & Mary Jones. Her father, a sailor, died at sea when she was too young to remember him, leaving 2 children, Rebecca & an older brother. Her mother, a loyal member of the Church of England, conducted a school for little girls in her home. Eager for Rebecca to become a teacher, her mother made sure that her daughter obtained a good education.

As a girl “romping Becky Jones” often attended Friends meetings with her playmates. The Quakers (or Religious Society of Friends) had formed in England in 1652, around a charismatic leader, George Fox (1624-1691). Many saw Quakers as radical Puritans, because the Quakers carried to extremes many Puritan convictions. They stretched the sober deportment of the Puritans into a glorification of "plainness." They expanded the Puritan concept of a church of individuals regenerated by the Holy Spirit to the idea of the indwelling of the Spirit or the "Light of Christ" in every person. Such teaching struck many of the Quakers' contemporaries as dangerous heresy.

Early Quaker Meeting

Quakers were severely persecuted in England for daring to deviate so far from orthodox Christianity. By 1680, 10,000 Quakers had been imprisoned in England; & 243 had died of torture & mistreatment in the King's jails. This reign of terror impelled Friends to seek refuge in New Jersey, in the 1670s, where they soon became well entrenched.

In 1681, when Quaker leader William Penn (1644-1718) parlayed a debt owed by Charles II to his father into a charter for the province of Pennsylvania, many more Quakers were prepared to grasp the opportunity to live in a land where they might worship freely. By 1685, as many as 8,000 Quakers had come to Pennsylvania. Although the Quakers may have resembled the Puritans in some religious beliefs & practices, they differed with them over the necessity of compelling religious uniformity in society.

Quaker Synod Meeting

When little Rebecca Jones began to refrain from such “ornamental branches” of her studies as music & dancing, her mother realized the that Quaker influence was striking deeper than she liked & sought to thwart it. The conflict wore heavily on Rebecca, who was also undergoing an intense inner struggle to surrender her own will to God’s. This she eventually achieved, aided by encouragements in 1755, from a visiting English Friend, Catherine Peyton.

After long hesitation Rebecca Jones in 1758, at 19, began to speak in the Friends meetings for worship, an open indication of her adoption of the Quaker faith. Two years later her gift in the ministry was “acknowledged” by her meeting, her mother thereupon becoming reconciled to the daughter’s decision.

Rebecca Jones thus became one of the laymen & women by whom the Quaker ministry has traditionally been performed. For over 20 years, she combined this ministry with teaching her mother’s school, which she too over upon her mother’s illness & death in 1761, though her inclination had been to find some other means of livelihood. She proved an able & respected schoolmistress.

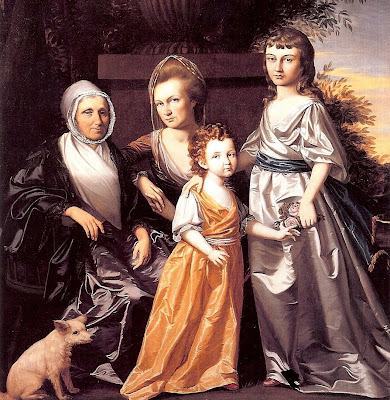

Early Quakers

She was a devoted friend of the famous Quaker minister John Woolman, who once penned mottoes for her pupils’ writing lessons. She retained, in her unassuming way, a certain “queenly dignity,” as well as an easy & gracious manner. These qualities enhanced the effectiveness of her speaking. Among women of her time she stood out for her intellectual capacity, quick wit, strength of character, & “sanctified common sense.”

In 1784, while at the height of her power as a preacher, Rebecca Jones gave up her school & laid before her monthly meeting her wish to visit Friends in England, a concern she had long cherished. Credentials were granted, & she sailed with 6 other Friends from Philadelphia. So impressed was the captain, Thomas Truxtun, later a naval here of the war with France, that he declared in London he had brought over an American Quaker lady who possesses more sense than both Houses of Parliament.

On arriving, the Friends sent straight to the Yearly Meeting, where a petition, long endorsed by American Friends, to establish a woman’s meeting for discipline, with more powers that the women’s meeting had had previously, was about to be presented to the men’s meeting. Rebecca Jones was instrumental in securing its approval.

Silhouette of Rebecca Jones. Early Quakers objected to having their portraits drawn or painted, but likenesses drawn from tracing a shadow casting and trimming out the resulting shape were considered acceptable by the church.

During the next 4 years, with a succession of the ablest women Friends as companions, she traversed the length & breadth of England & also visited Scotland ,Wales, & Ireland. She impressed her hearers with the need for a revival of zeal & simplicity. Her memorandum of her tour enumerated 1,578 meetings for worship & discipline & 1,120 meetings with Friends in the station of servants, apprentices, & laborers (for whom she had a special concern), besides innumerable religious family visits. Her message particularly reached the young. Under a sense of “fresh & sure direction,” she returned home in the summer of 1788.

Having given up teaching, she now earned her living by keeping a little ship which her English friends kept supplied with “lawns & cambrics & find cap muslins.” She continued he preaching, frequently attending yearly & quarterly meetings in various parts of the Northeastern states, especially in New Jersey & New England.

She fell ill in the yellow fever epidemic of 1793, in which 4,000 Philadelphians died, but lived to resume herm ministry & the wide correspondence which was a major activity of her later years. In the mid-1790s, she contributed her knowledge of Friends education in England to the founding of Westtown (Pa.) School, a boarding school which opened in the spring of 1799, patterned after the Ackworth Friends School in Yorkshire.

Silhouette of Rebecca Jones.

For more than 50 years Rebecca Jones was a trusted counselor & informal almoner, “eminent for leading the cause of the poor.” Her home was always open to those in trouble or wishing her advice; possessing “singular penetration on discovering cases of distress, and delicacy in affording relief” (Allinson, p. 256), she was also a frequent visitor at Friends almshouses.

In 1813, she suffered an attack of typhus fever; & for the last 5 years of her life, she was confined almost entirely to her home, where she was devotedly card for by Bernice Chattin Allinson, a young widow whom she had taken in as a daughter. Rebecca Jones died in Philadelphia in 1818, in her 79th year. She was buried in the Friends ground on Mulberry (now Arch) Street on the morning of the yearly meeting of ministers & elders.

This posting based, in part, on information from Notable American Women edited by Edward T James, Janet Wilson James, Paul S Boyer, The Belknap Press of Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 1971

.

Rebecca Jones (1739-1818), Quaker minister, was born in Philadelphia, the only daughter of William & Mary Jones. Her father, a sailor, died at sea when she was too young to remember him, leaving 2 children, Rebecca & an older brother. Her mother, a loyal member of the Church of England, conducted a school for little girls in her home. Eager for Rebecca to become a teacher, her mother made sure that her daughter obtained a good education.

As a girl “romping Becky Jones” often attended Friends meetings with her playmates. The Quakers (or Religious Society of Friends) had formed in England in 1652, around a charismatic leader, George Fox (1624-1691). Many saw Quakers as radical Puritans, because the Quakers carried to extremes many Puritan convictions. They stretched the sober deportment of the Puritans into a glorification of "plainness." They expanded the Puritan concept of a church of individuals regenerated by the Holy Spirit to the idea of the indwelling of the Spirit or the "Light of Christ" in every person. Such teaching struck many of the Quakers' contemporaries as dangerous heresy.

Early Quaker Meeting

Quakers were severely persecuted in England for daring to deviate so far from orthodox Christianity. By 1680, 10,000 Quakers had been imprisoned in England; & 243 had died of torture & mistreatment in the King's jails. This reign of terror impelled Friends to seek refuge in New Jersey, in the 1670s, where they soon became well entrenched.

In 1681, when Quaker leader William Penn (1644-1718) parlayed a debt owed by Charles II to his father into a charter for the province of Pennsylvania, many more Quakers were prepared to grasp the opportunity to live in a land where they might worship freely. By 1685, as many as 8,000 Quakers had come to Pennsylvania. Although the Quakers may have resembled the Puritans in some religious beliefs & practices, they differed with them over the necessity of compelling religious uniformity in society.

Quaker Synod Meeting

When little Rebecca Jones began to refrain from such “ornamental branches” of her studies as music & dancing, her mother realized the that Quaker influence was striking deeper than she liked & sought to thwart it. The conflict wore heavily on Rebecca, who was also undergoing an intense inner struggle to surrender her own will to God’s. This she eventually achieved, aided by encouragements in 1755, from a visiting English Friend, Catherine Peyton.

After long hesitation Rebecca Jones in 1758, at 19, began to speak in the Friends meetings for worship, an open indication of her adoption of the Quaker faith. Two years later her gift in the ministry was “acknowledged” by her meeting, her mother thereupon becoming reconciled to the daughter’s decision.

Rebecca Jones thus became one of the laymen & women by whom the Quaker ministry has traditionally been performed. For over 20 years, she combined this ministry with teaching her mother’s school, which she too over upon her mother’s illness & death in 1761, though her inclination had been to find some other means of livelihood. She proved an able & respected schoolmistress.

Early Quakers

She was a devoted friend of the famous Quaker minister John Woolman, who once penned mottoes for her pupils’ writing lessons. She retained, in her unassuming way, a certain “queenly dignity,” as well as an easy & gracious manner. These qualities enhanced the effectiveness of her speaking. Among women of her time she stood out for her intellectual capacity, quick wit, strength of character, & “sanctified common sense.”

In 1784, while at the height of her power as a preacher, Rebecca Jones gave up her school & laid before her monthly meeting her wish to visit Friends in England, a concern she had long cherished. Credentials were granted, & she sailed with 6 other Friends from Philadelphia. So impressed was the captain, Thomas Truxtun, later a naval here of the war with France, that he declared in London he had brought over an American Quaker lady who possesses more sense than both Houses of Parliament.

On arriving, the Friends sent straight to the Yearly Meeting, where a petition, long endorsed by American Friends, to establish a woman’s meeting for discipline, with more powers that the women’s meeting had had previously, was about to be presented to the men’s meeting. Rebecca Jones was instrumental in securing its approval.

Silhouette of Rebecca Jones. Early Quakers objected to having their portraits drawn or painted, but likenesses drawn from tracing a shadow casting and trimming out the resulting shape were considered acceptable by the church.

During the next 4 years, with a succession of the ablest women Friends as companions, she traversed the length & breadth of England & also visited Scotland ,Wales, & Ireland. She impressed her hearers with the need for a revival of zeal & simplicity. Her memorandum of her tour enumerated 1,578 meetings for worship & discipline & 1,120 meetings with Friends in the station of servants, apprentices, & laborers (for whom she had a special concern), besides innumerable religious family visits. Her message particularly reached the young. Under a sense of “fresh & sure direction,” she returned home in the summer of 1788.

Having given up teaching, she now earned her living by keeping a little ship which her English friends kept supplied with “lawns & cambrics & find cap muslins.” She continued he preaching, frequently attending yearly & quarterly meetings in various parts of the Northeastern states, especially in New Jersey & New England.

She fell ill in the yellow fever epidemic of 1793, in which 4,000 Philadelphians died, but lived to resume herm ministry & the wide correspondence which was a major activity of her later years. In the mid-1790s, she contributed her knowledge of Friends education in England to the founding of Westtown (Pa.) School, a boarding school which opened in the spring of 1799, patterned after the Ackworth Friends School in Yorkshire.

Silhouette of Rebecca Jones.

For more than 50 years Rebecca Jones was a trusted counselor & informal almoner, “eminent for leading the cause of the poor.” Her home was always open to those in trouble or wishing her advice; possessing “singular penetration on discovering cases of distress, and delicacy in affording relief” (Allinson, p. 256), she was also a frequent visitor at Friends almshouses.

In 1813, she suffered an attack of typhus fever; & for the last 5 years of her life, she was confined almost entirely to her home, where she was devotedly card for by Bernice Chattin Allinson, a young widow whom she had taken in as a daughter. Rebecca Jones died in Philadelphia in 1818, in her 79th year. She was buried in the Friends ground on Mulberry (now Arch) Street on the morning of the yearly meeting of ministers & elders.

This posting based, in part, on information from Notable American Women edited by Edward T James, Janet Wilson James, Paul S Boyer, The Belknap Press of Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 1971

.

+MESDA1st-gallery-art.com.jpg)

.+Elizabeth+Allston+(Mrs.+William+H.+Gibbes)..jpg)

.+Charlotte+Pepper+(Mrs.+James+Gignilliat).+Colonial+Williamsburg+Foundation..jpg)